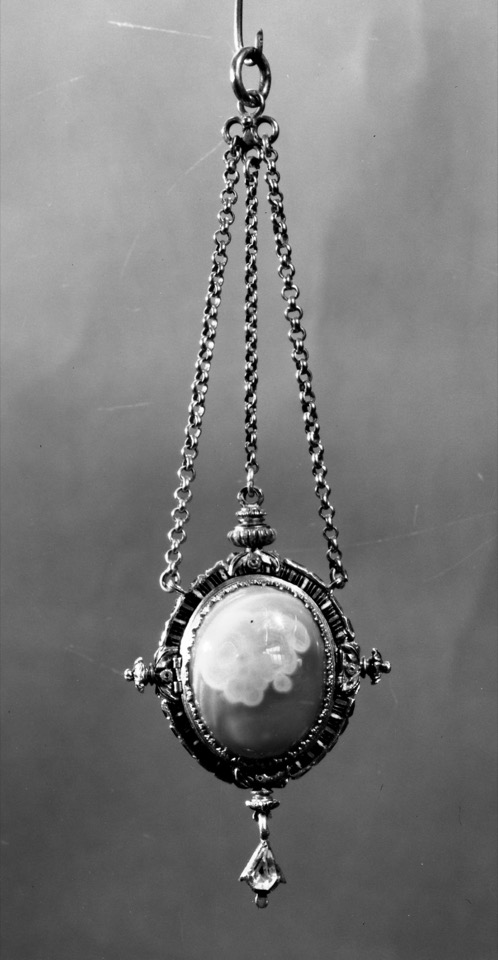

Bead, Moses and the Tablets of the Law

WB.184

1500–1600, altered 1800–1898 •

locket

Curator's Description

Oval locket; gold; sides of convex plates of grey agate; projecting edge with enamelled design set on outside with square table rubies; four bosses at top, bottom and sides; standing figure of Moses in gold, partly enamelled, holding two tablets of Law inscribed in Hebrew; three modern suspension chains; pear-shaped faceted diamond at base.

This object was collected and bequeathed to the British Museum by Ferdinand Anselm Rothschild.

How big is it?

3.5 cm wide, 11.2 cm high, 2.3 cm deep, and it weighs 28.2g

Detailed Curatorial Notes

Text from Tait 1986:-

Origin: Uncertain; perhaps French, apparently much modified. The pendant drop, chains and 'cartouche' are 19th-century additions; the figure may not be original.

Provenance: None is recorded.

Commentary: There are a number of similar agate beads with gold mounts designed to open in this fashion and to reveal a single figure or, more exceptionally, a miniature scene. The best documented example that has survived is in the Imperial Hapsburg Collections in Vienna; it is the famous onyx rosary of the early sixteenth century which

was recorded in the Schatzkammer Inventory of 1750 (no. 17) and has been fully described and illustrated in F. Eichler and E. Kris, ‘Die Kameen im Kunsthistorisches Museum’, Vienna, 1927, pp. 166-8, no. 390, pl. 54, fig. 72. The ten oval onyx beads in gold enamelled mounts are of a similar size and open to reveal a single figure in each half of the bead; these twenty figures are shell cameos carved in relief. The effect, however, is comparable to that of the Moses figure in the Waddesdon agate bead because in most cases the single figure is represented standing motionless and holding the appropriate attribute. Significantly, all the figures are either Apostles or, like St Veronica, part of the story of the Passion of Christ. Similarly, the larger paternoster bead opens to reveal scenes from the New Testament (the Life of the Virgin), even more splendidly worked, including two gold enamelled scenes executed in the translucent email en basse taille technique. In 1927 this rosary was tentatively attributed to a French workshop.

Another rosary in the Pierpont Morgan Gift of 1917 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is composed of nine oval agate beads that open to reveal scenes, chiefly from the Infancy of Christ, all executed in enamelled gold with the figures in relief against a three-dimensional setting (G.C. Williamson, ‘Catalogue of the Collection of Jewels and Precious Works of Art, The Property of J. Pierpont Morgan’, London, 1910, pp. 24-6, no. 13, pls 8-9; also, a virtually illegible photograph in Yvonne Hackenbroch, ‘Renaissance Jewellery’, Sotheby Parke Bernet Publications, London, New York and Munich, 1979, p. 315, fig. 823, where it is attributed to “Spain, c. 1510”.) There is a second rosary of similar character but complete with ten oval agate beads, a larger paternoster and a pendant cross - all made with gold enamelled mounts but with the scenes of the Passion of Christ inside the beads executed in pierced openwork reliefs without any backgrounds; it is preserved in the Musée du Louvre (see J. J. Marquet de Vasselot, ‘Orfèvrerie, Emaillerie et Gemmes’, Paris, 1914, p. 53, no. 284; illus. in colour in ‘The Great Book of Jewels’, eds E. and J. Heiniger, Lausanne, 1974, pl. 197). Both these rosaries lack a provenance; indeed, neither may be older than the nineteenth century, for both on technical and stylistic grounds they give rise to serious doubts about their authenticity.

A single bead of agate that has survived as a pendant jewel with three enamelled chains and a jewelled 'cartouche' is of greater relevance; it was sold at Christie's in 1961 without any provenance and was published soon afterwards as belonging to the tiny group of English mid-sixteenth-century jewels with figure scenes (see Hugh Tait, Historiated Tudor Jewellery, ‘Antiquaries Journal’, 1962, vol. XLII, pt. II, p. 226 ff., pl. XLVI, a; and more recently, A Somers Cocks and C. Truman, ‘The Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection’, London, 1984, p. 72, no. 4). This gold mounted spherical agate bead is different in its construction: the front half of the sphere opens in two equal segments to form a hinged triptych. It is unique in this respect. The central concave roundel contains a three-dimensional representation of the crowded Nativity scene with the Adoration of the Shepherds, whilst the left-hand 'wing' of the triptych has the Angel of the Annunciation in relief and the right-hand 'wing' has the kneeling Virgin, also in high relief, with the prie-Dieu in the background. This highly ambitious piece reveals strong Continental influences, as would be expected in England in the reign of Henry VIII and Mary Tudor, when goldsmiths and jewellers from the Netherlands are known to have been working in London and receiving Court patronage. In the 1984 publication of this unique pendant bead attention was drawn to the listing of similar devotional objects in the 1560 Inventory of the Jewels of the French Crown, but there is no indication where these pieces were made nor is there any suggestion that they were mounted as pendants. Nevertheless, it is helpful to quote all four related entries:

“551. Une pomme garnie de deux agathes dont l'une est taille d'une teste de mort, estimee xxx.

553. Une autre pomme d'agate qui s'ouvre dans laquelle y a ung Trepassement et un Assumption Nostre Dame, estimee xxx.

554. Une autre demye pomme d'agatte qui s'ouvre, dans laquelle y a ung Crucifiement, estimee xii.

555. Une autre d'agate, couverte d'ung cristal, ou il y a une Nostre Dame de pitie, estimee xii.”

The last two entries, one with the Crucifixion and one with Notre Dame de Pitie, may be the remaining fragments of two separate objects, although there is no suggestion that they are incomplete; indeed, no. 554 is said to open although it is only a 'demye pomme'. The first two (nos 551 and 553) in this 1560 Inventory seem to be listing beads of the type that were used for the grand rosaries, but that is not to say they could not have been mounted as devotional pendants, if fashion so demanded. Their use is not made clear in the 1560 Inventory. The unprovenanced example that opens like a triptych could have been subsequently adapted to become a pendant, because the design of the gold enamelled chains and gem-set 'cartouche' is not en suite with the agate bead and, indeed, appears to be of later date. The triptych bead, it must be emphasised, is enriched with gold mounts set with table-cut rubies - a most exceptional feature for an agate bead of this type.

Two single beads of similar construction and character have survived in America: the agate bead with the gold enamelled Annunciation scene (inside) in the Hispanic Society of America, New York (see Priscilla E. Muller, ‘Jewels in Spain, 1500 – 1800’, The Hispanic Society of America, New York, 1972, p. 62, col. frontispiece, for interior, and fig. 73 for exterior) and, secondly, the less convincing agate bead with the gold enamelled figures of Pyramus and Thisbe inside (published in Diana Scarisbrick, in ‘Jewellery, Ancient to Modern’, exh. cat., Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, 1979, p. 189, no. 514).

Apart from the last-mentioned, all the surviving examples have New Testament figures or scenes inside the beads of hardstone. The figure of Moses would, of course, be wholly inappropriate in a rosary bead and, no doubt, it is for that reason that the earlier publications of this piece have described it as a locket. Indeed, a jewel with the figure of Moses holding the Tables of the Law would not seem to be out of keeping with Renaissance practice; for example, in England the 1542-6 Inventory of Jewels belonging to Princess Mary, daughter of Henry VIII, included “Oon Broche of golde of the History of Moyses set with ii little diamonds”, whilst the 1560 French Royal Inventory lists a hat-jewel: “Une enseigne d'une Moyse garny de tables de diamantz, estimee LX.” However, an examination of the interior of this bead reveals that the opaque blue enamel on the mount has been damaged on either side of the projecting tiny platform that supports the figure of Moses. The suggestion is now tentatively made that the platform and the figure of Moses have been inserted more recently and the bead converted into a pendant locket.

Finally, it should be noted that the gold enamelled pendant below this agate bead with Moses is stylistically unrelated to the rest of the pendant. Not only is its shape unparalleled in Renaissance jewellery but the enamelled decoration on the reverse is of a much later period. The faceted stone in this little pendant drop is not a diamond (as previously published) but a rock-crystal variety of quartz. It seems probable that the pendant drop was added when the agate bead was converted into a pendant locket and the figure of Moses was inserted.

Bibliography

- Charles Hercules Read, ‘The Waddesdon Bequest: Catalogue of the Works of Art bequeathed to the British Museum by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild, M.P., 1898’, London, 1902, no. 184

- O.M. Dalton, ‘The Waddesdon Bequest’, 2nd edn (rev), British Museum, London, 1927, no. 184

- Hugh Tait, 'Catalogue of the Waddesdon Bequest in the British Museum. 1., The Jewels', British Museum, London, 1986, no. 49, pl. XXVIII, figs. 211-212.

- Read 1902: Read, Charles Hercules, The Waddesdon Bequest. Catalogue of the Works of Art Bequeathed to the British Museum by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild, M.P., 1898, London, BMP, 1902

- Dalton 1927: Dalton, Ormonde Maddock, The Waddesdon Bequest : jewels, plate, and other works of art bequeathed by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild., London, BMP, 1927

- Tait 1986: Tait, Hugh, Catalogue of the Waddesdon Bequest in the British Museum; I The Jewels, London, BMP, 1986